In a VC fundraising landscape increasingly populated with mega funds, what does the rise to $500M look like — and what’s the appeal of these giants for LPs?

2020 has undoubtedly been the year of the Mega Fund.

As both Pitchbook and Silicon Valley Bank recently reported, venture capital vehicles with more than $500M in assets have absolutely dominated the fundraising landscape since the pandemic took hold. SVB’s latest State of the Markets showed these mega funds have accounted for 70% of capital raised in 2020, up from 43% in 2019 and 44% in 2018. And Pitchbook-NVCA’s latest Venture Monitor revealed that the number of mega funds closed in the first half of 2020 nearly equaled the tally for all of 2019.

Back in May, we identified the first signs of the expanding role of mega funds and suggested that LPs were being pushed by pandemic uncertainty to flock to ‘known’ venture brands. With full 1H numbers confirming the rush to established giants, we wanted to revisit the topic and take a closer look at the profiles of mega funds, tracking and assessing their rise to $500M.

How Common are Mega Funds, Really?

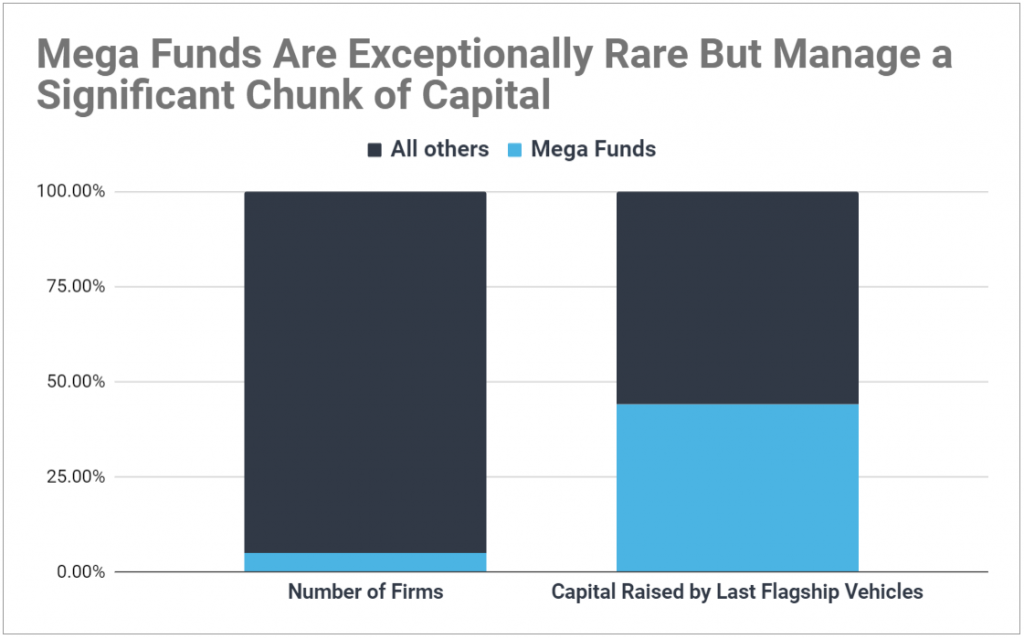

First, it’s worth iterating just how unlikely it is that any given VC will ever reach the $500M threshold. Of the more than 1,500 active VC firms we track, fewer than 5% have ever raised a $500M flagship vehicle.

Yet with each one pulling in at least 10 times the capital of the median $50M fund, this sliver of the venture world manages to account for more than 44% of capital being deployed across the most recent flagship vehicles. And they account for more than 62% of total capital under management.

Clearly mega funds have an outsized influence on the allocation of venture dollars, and as the data shows, the pandemic is only accelerating their control.

Getting to $500M: How Long Does it Take?

Raising half a billion dollars is an incredibly resource and time intensive feat. Not only does it require being tapped into the right networks (and a lot of the right networks), but also that the GPs (or investor relations team) raising this massive sum dedicate significant time to the fundraising trail. GPs must meet with many institutional investors, craft convincing pitch decks and robust deal rooms, manage perspectives, and convert soft commitments into hard ones — it’s a full-time job and then some.

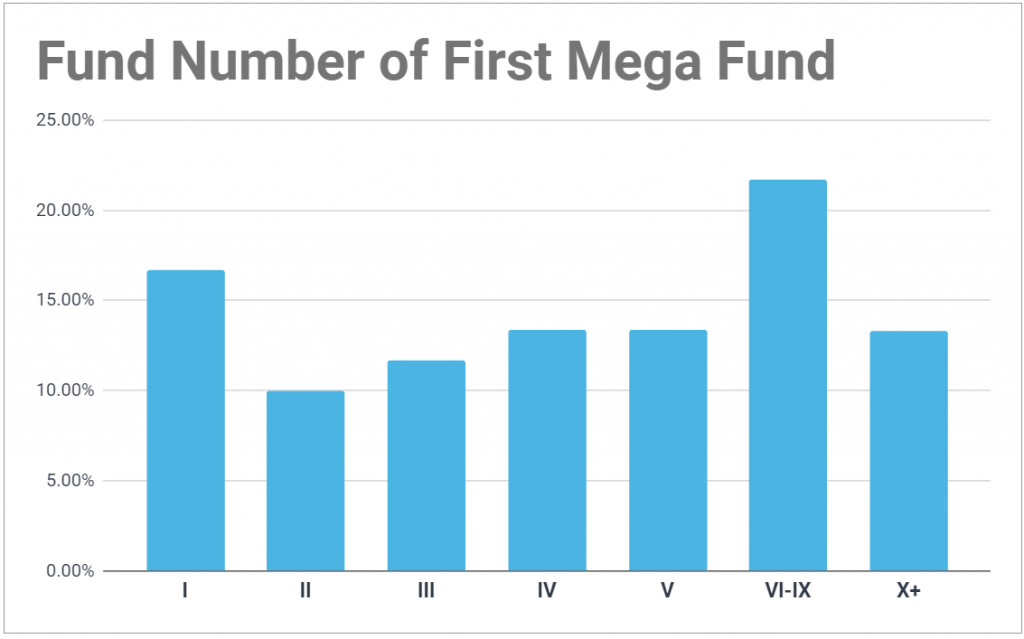

Consequently, it’s surprising to find that one out of six VCs who raise a mega fund do so on their first fund. That’s more than 16% jumping straight to mega fund status — no investing track record as a firm, no stream of management fees from an earlier fund to cover travel expenses and salaries, no existing investors or previous pitch deck to build off. Straight to $500M.

Of course, this rare breed of firm is rarely new to investing. They typically bring track records from prior VCs or investment firms, and are sometimes spinouts, like Lee Fixel who left Tiger Global to debut Addition’s modest $1.3B fund. Other times they bring the backing of corporates or other deep-pocketed investors capable of funding a significant portion of the $500M+ — like the coalition of billionaires backing Breakthrough Energy Ventures, or the group of energy and utility companies behind Energy Impact Partners.

But when not a debut vehicle, mega funds are distributed quite evenly across Fund II to V, so that 65% of VCs who reach mega fund status do so by their fifth flagship vehicle. A handful of firms don’t cross the $500M threshold until their tenth fund or later, though the norm certainly seems to lean earlier in a firm’s lifetime.

How Big is the Jump?

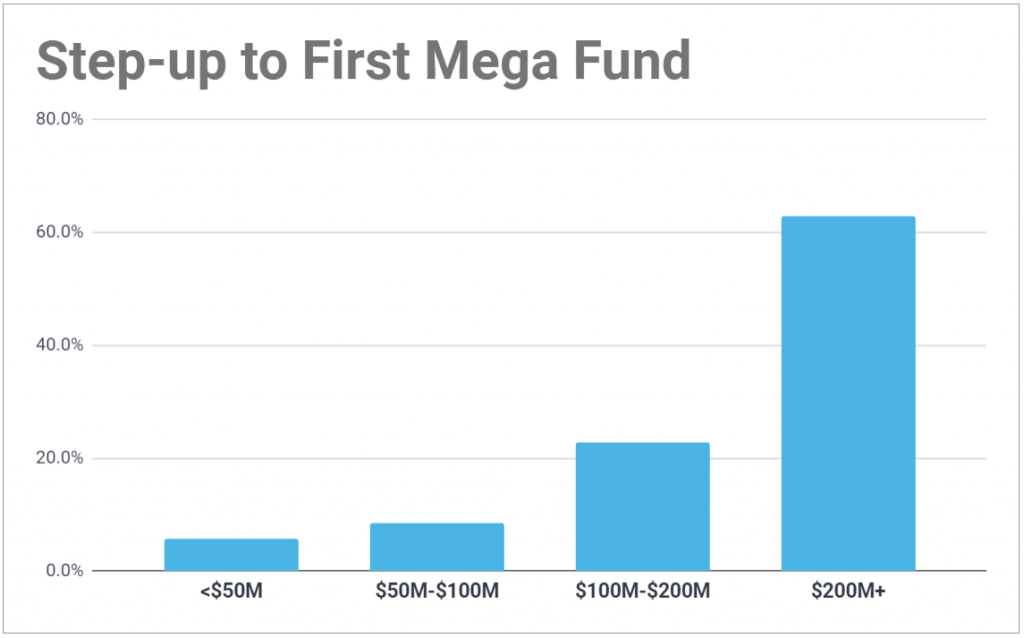

Excluding debut funds, the median step-up to a VC’s first mega fund is a significant $200M over their previous raise, with the average skewed upwards to $314M. Evidently, the rise to mega fund status is (by and large) a very ambitious leap rather than a gradual climb. Fewer than 15% of VCs have a step-up of less than $100M to their first mega fund, and just 6% ease in with a $50M step-up or less.

Interestingly, the $200M+ jump that 63% of mega funds make seems to be driven not by a wildly oversubscribed previous fund, but rather by simply meeting their last targets. The median fundraising performance of the flagship vehicle prior to a first mega fund is 100% (indicating a raise that exactly equals the original target).

While meeting a target is certainly reason for some degree of a confidence boost (since our data estimates about half of all flagship vehicles never report hitting or exceeding their original targets), it’s nonetheless a bold move to then vault up to $500M.

But apparently not so bold as to be a misjudgement: the median fundraising performance of a VC’s first mega fund is also 100%. Although the average is pulled slightly down to 95%, it’s clear that when a firm sets its sights on mega fund status, it rarely falls short.

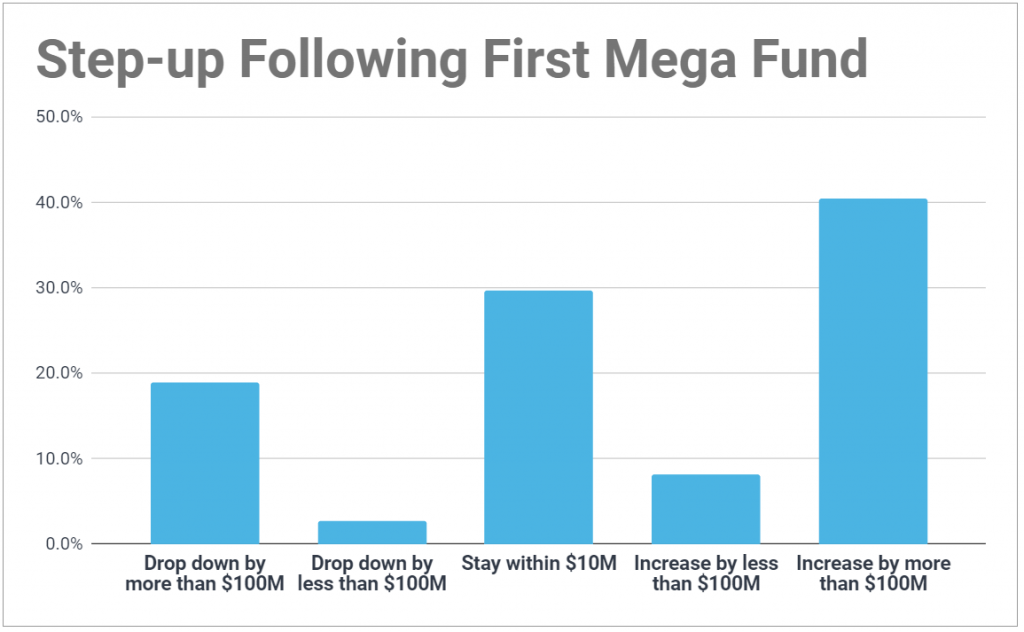

And what happens after a firm raises that first mega fund? While 30% maintain the same fund size and keep their next vehicle within $10M of their first mega fund, the remainder diverge into two distant camps. Approximately 41% of mega funds continue to grow (and grow significantly), jumping at least another $100M with their next fundraise. Another 20%, meanwhile, drop down by more than $100M, either being unable to raise a second mega fund or deciding the elusive threshold of half a billion dollars doesn’t actually align with their strategy (e.g. for a seed-stage conviction-style firm).

Driving the Rise to $500M: More LPs or Greater Check Sizes?

When a VC makes that grand jump to $500M, is the growth in fund size driven by a drastic increase in the number of participating LPs or by a drastic increase in the average check each LP contributes? In short, both.

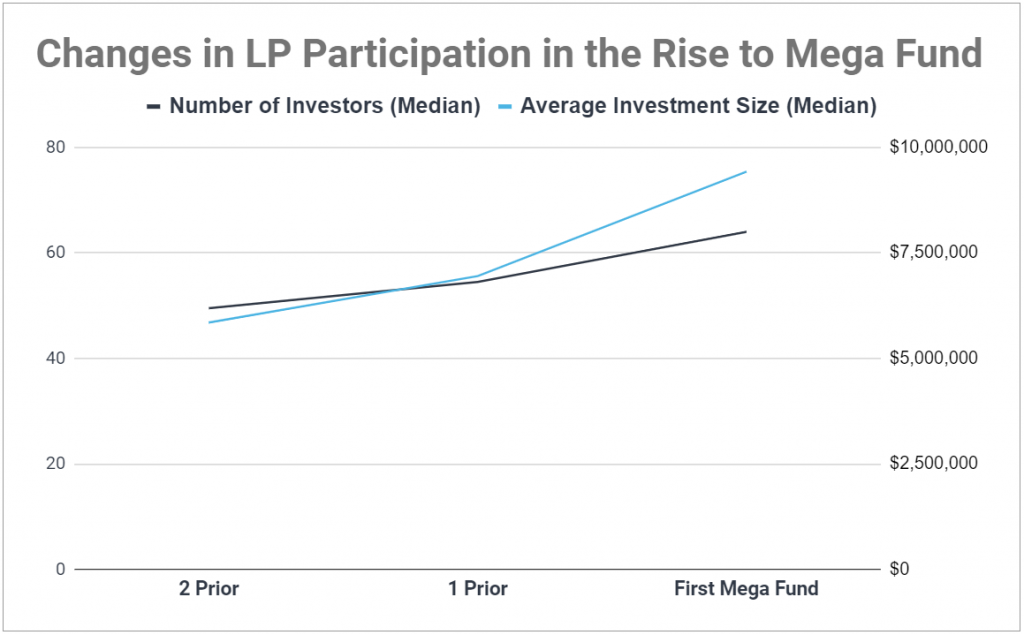

Tracking changes in LP participation in the vehicles preceding a firm’s first mega fund, we see a clear increase in both the number of LPs and the average investment each LP makes. While the median number of LPs participating in a firm’s first mega fund is 64, that number sits at 54 for the vehicle prior to the first mega fund and just 49 for the vehicle prior to that. Similarly, while the median first mega fund has an average check size of $9.4M, two vehicles prior has a median check size of $5.8M.

Although both factor into play, the greater proportional increase in check size (a 62% increase compared to a 31% increase in the number of LPs) suggests larger investments are the stronger driver.

Does Fundraising Performance Equate to Returns Performance?

Mega funds obviously have no issue raising capital.

They typically rise to the $500M mark early in the firm’s life, often targeting an ambitious step-up that they successfully close while convincing more and more LPs to invest increasingly large sums. Fundraising is their forte.

But do these firms hold the same premium when it comes to producing returns? Are the most successful fundraisers also the most successful investors?

In many cases, the data says no — smaller funds are the real outperformers.

So what’s the appeal of a mega fund if not exceptional returns? For many, it’s the perception of security.

Mega funds offer investors what feels like a safe bet — no one gets fired for choosing the half billion dollar fund that a hundred other big-ticket investors chose. And consistent returns (even those on par with an index fund) become incredibly persuasive in the face of a global pandemic.

But with VC generally being the high-risk, high-returns sleeve of a broader investment strategy, there’s an obvious question to ask: is venture a part of your portfolio to be consistently mediocre, or to be occasionally exceptional?

For Institutional LPs, the Math on Mega Funds Works Better

Beyond the sense of security and stature that mega funds bring, there’s a second appeal for many big-ticket institutional LPs — investing in mega funds is just easier.

Why? For one, diligencing VC firms and hiring managers takes time. And with the average institutional LP allocating just 4-6% of their total portfolio (of about 30 managers) to venture, it’s a lot quicker to find one really big VC than to diligence and hire dozens of emerging managers. Combined with the risk and binary reward profile of venture, where there are a lot of losers, LPs just have a simpler time diligencing big-name managers with at least a mediocre track record than new players piloting smaller funds.

More importantly, the math on mega funds works better. A $1B family office or a $10B pension may look to place at least $25M-$50M in each venture fund, but they also usually want to remain less than 10% of the total LP backing of each fund. For VCs targeting anything less than a mega fund, this math is impossible.

The result is that big-ticket LPs often don’t see emerging managers (even outperforming ones) as worthwhile — how could such a small drop “move the needle” in such a large bucket? Established mega funds are simply the most time efficient way for these LPs to invest in venture.

And that’s why VC firms raised just $46.3B last year when we estimate there should’ve been nearly $1T available. The LPs managing the most capital weren’t willing to put it to work.