Although less talked about, non-flagship funds (growth funds, SPVs, syndicates, etc.) are a significant source of capital for many VC firms — in this post, we take a detailed look at how these vehicles line up next to the flagship market, their relative prevalence, and the kinds of firms that tend to leverage each.

Historically, venture capital fundraising has typically centered around what are often referred to as “flagship funds.” These are a traditional VC’s primary investment vehicle, designed to make new (and, for many, follow-on) investments across a variety of bets — they are the fund a GP takes on the 12-18 month fundraising trail, that’s reported on in venture media, and that requires meticulously thought-out pitch decks, significant engagement with an endless list of prospective LPs, and a full-time commitment for months.

And while alternative structures have always been leveraged by some, in recent years we’ve witnessed an increasing number of VC firms experiment with non-flagship funds: growth or opportunity funds, SPVs, syndicates, and co-investment vehicles, among others. Whether it’s to offer existing LPs additional exposure to one highly attractive company in the VC’s main portfolio, or to inject cash into the highest performing subset of the portfolio, or to build a formal relationship with a key LP that missed the flagship raise, these alternatively structured funds are all created for a specific purpose that complements the VC’s main investment activities.

Some VCs have even eschewed the traditional flagship fund altogether, with our estimates suggesting over 2% of VCs in the US operate exclusively under alternative fund structures, like SPVs.

Simultaneously yet at the opposite end of the venture capital life cycle, SPACs have exploded in prevalence — accounting for 80% of money raised in April IPOs compared to the 9% average of the past decade. And some of these SPACs happen to be led by well established VCs. The rise of SPACs represents yet another component to the venture capitalist’s toolkit, albeit as a liquidity mechanism for VCs and founders.

With the growing complexity and diversity of VC funds facing LPs, we thought we’d take a look at the non-flagship market to quantify its significance next to the flagship market, assess its role in venture capital, and profile the VCs behind these alternative structures.

Quantifying the Non-Flagship Market

Non-flagship funds are hardly a small part of venture capital.

In 2019, non-flagship funds raised a total of $13.2 billion across 190 vehicles. Adding their weight to the $41B flagship market expands total venture capital raised in 2019 by a significant 32%, and means non-flagship funds account for about a quarter of total VC assets raised for the year.

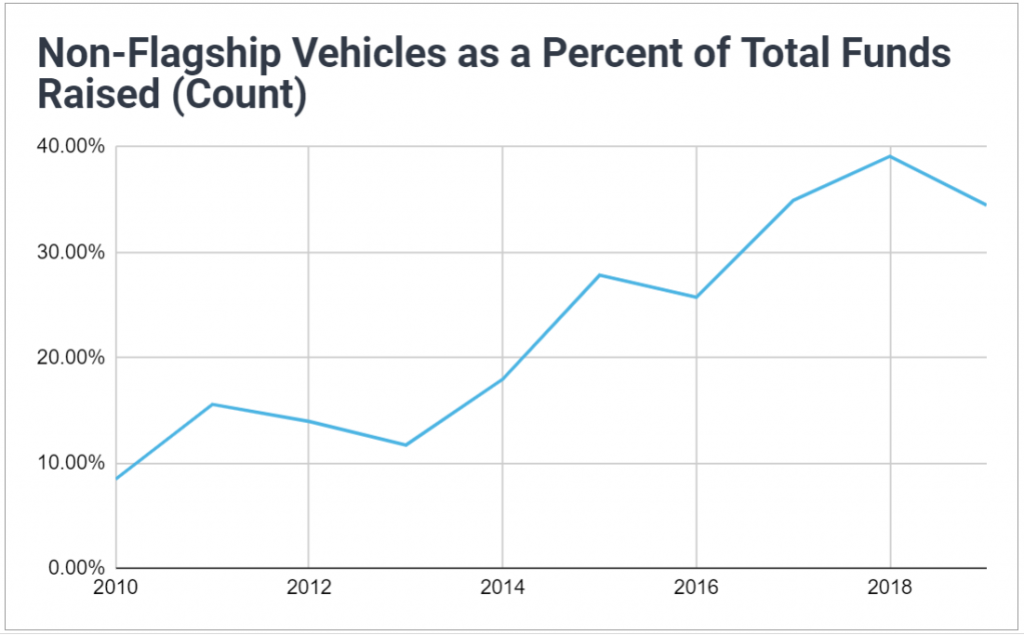

They’ve also been outpacing the growth of the flagship market since 2010, resulting in their increasing share of the VC fund count. Whereas just 10% of venture capital vehicles raised in 2010 leveraged a non-flagship structure, that number stood well above a third by the end of the decade.

Not All Non-Flagships Funds are Created Equal

Of course, since different non-flagship funds are designed for different purposes, there’s quite a bit of variation within the alternative-structure market.

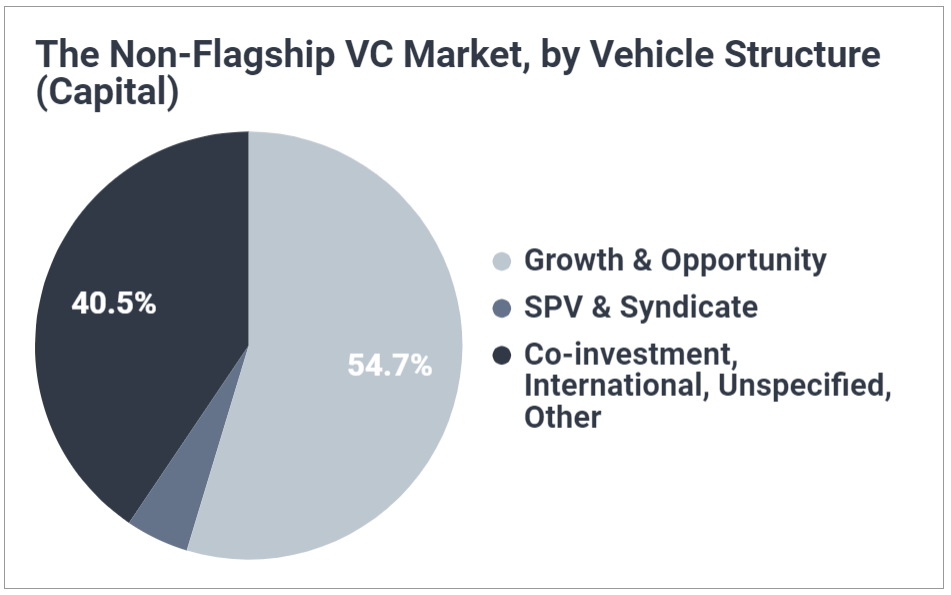

Leading the non-flagship market in terms of capital, Growth and Opportunity funds are often raised directly alongside a VC’s flagship fund. Sometimes referred to as a “Select” fund, this class of vehicle typically invests at a later stage than the VC’s main fund and is leveraged to make significant follow-on investments in the high-performing (or highly capital intensive) subset of the main portfolio. The capital raised for this kind of vehicle is allocated to startups that have already been test-driven (de-risked) by the firm’s flagship fund, and consequently pull in a hefty chunk of capital for the VCs who raise them: the average Growth / Opportunity fund raises $53.6M, trending upwards to $69.5M in 2019.

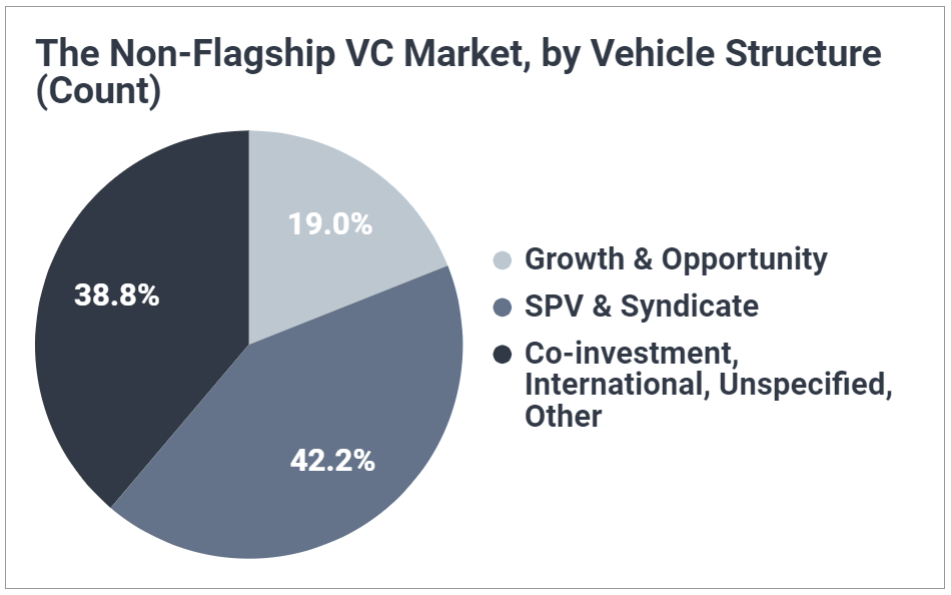

Since 2015, Growth & Opportunity funds have contributed just over half (54%) of all capital raised by the non-flagship market. This is due largely to their above-average size, as they account for just 19% of all vehicles raised over the same period.

By contrast, special purpose vehicles (SPVs) and Syndicates are created by VCs to allow one LP or a group of LPs to gain exposure to a single, specific company. While sometimes being used to inject cash into a company from within the VC’s primary portfolio, this class of vehicle can also be used to invest in a riskier startup that might not fit within the primary portfolio — allowing the VC to avoid a drag on the reported returns of the flagship fund if the company fails while offering potentially significant upside for select LPs if it succeeds. As such, these types of vehicles tend to be smaller, averaging $5.6M and trending slightly upwards to $6.2M in 2019.

Since 2015, SPVs & Syndicates have contributed just 5% of capital raised by the non-flagship market but are the most common type of non-flagship fund, accounting for 42% of vehicles over the same period.

The rest of the non-flagship market is a wide mix of funds, ranging from co-investment vehicles that allow LPs not included in the flagship raise to invest alongside the flagship portfolio (thus often being a smaller vehicle), to international funds leveraged by global VCs to separate their portfolio by geographic region (thus being larger vehicles), to unspecified funds filed separately from a clear flagship vehicle but under an obscure moniker (ranging in size).

Who’s Raising Non-Flagships?

We estimate that about a quarter (25.4%) of venture capital firms in the US have leveraged at least one of these alternative vehicle structures. Among VCs using non-flagship funds, the median firm raises a significant 19.5% of its total AUM through side funds. The average AUM being raised through non-flagship vehicles is also skewed upwards to 32.8%, indicating there’s even a subset of outlier firms deriving well over a third of their capital from alternative structures.

VCs raising non-flagship funds tend to be both older and larger than those sticking to flagships.

Whereas VCs with at least one non-flagship fund have a core fund averaging $210.5M, firms without any alternatively-structured funds average just $105.5M. Growth & opportunity funds are particularly the realm of big funds, with the average firm raising $310.4M through its latest flagship. And, VCs that have raised some form of a non-flagship vehicle are nearly 5 times more likely than others to have made it to a Fund V or beyond.

Additionally, firms that raise non-flagship investment vehicles tend to be slightly more successful at raising capital for their core VC funds. On average they close 75% of their target raise, while firms without side funds average 68%. This suggests non-flagships are not typically used as a piecemeal investment tool following a disappointing flagship raise.

| Average flagship fund size | Percent on Fund V+ | Average Percent of Flagship Target Raised | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firms that raised a non-flagship vehicle | $210,454,985 | 29.2% | 75.2% |

| Firms that only raise flagship vehicles | $105,501,842 | 5.8% | 68.0% |

SPACs Aside: Different yet rapidly emerging part of the venture toolkit

Those who follow the public markets are likely aware that SPACs — special purpose acquisition companies — are all the rage in 2020 (174 as of this publication date). Unlike opportunity funds, syndicates, sidecars, and the other non-flagship funds mentioned above, SPACs are really a liquidity mechanism. As with an IPO, a Dutch Auction, or a Direct Listing, SPACs are a way to take a company public and create liquidity for that company’s investors. SPACs also have a wide range of managers behind them…ranging from the likes of former U.S. congressman Paul Ryan to Apollo Global to legendary athlete Shaquille O’Neill.

But as it relates to VC firms, it’s worth noting that a small yet growing roster of VCs have created their own SPACs to take companies public. Venture firms like Lux, First Mark and Ribbit Capital have entered the SPAC game.

This represents yet another vehicle in the venture toolbox. Which could prove to be a powerful asset or a major distraction. (It also represents a unique way for VCs to encroach on the fees traditionally captured by investment bankers via IPOs.) The details of SPACs in venture and ‘going public’ are a subject for a future article. But we’ll note that thus far (and logically so), VC-managed SPACs are largely the exclusive domain of mega funds.

Being Thoughtful When Incorporating Non-Flagships in a Broader Investment Strategy

As if sourcing, diligencing, and selecting a VC firm wasn’t complicated enough, LPs are increasingly being faced with the task of navigating the world of alternative vehicle structures. After finding the right manager, it can be easy to brush off the significance of deciding which of a VC’s funds to back — how different can each be when they’re managed by the same team? But with non-flagship vehicles being so specialized, this question becomes incredibly consequential.

Many times, non-flagships offer different fee structures (or even no fees), allowing more capital to go to work at a lower cost. Others feed a specific one-off deal, strategy, or geography that can present a unique opportunity to adjust exposures within a broader portfolio. And yet others allow an LP to gain experience with something resembling a direct deal.

But when presented with a non-flagship fund (even by a venture firm already in your portfolio), it’s crucial to diligence that opportunity the same way a new manager would be diligenced, asking how the fund fits into your broader investment strategy and how it’ll affect ultimate returns.

Because as tempting as a low-fee, exclusive SPV may be, is it a vehicle being offered to boost returns to LPs or the GP’s pockets?