An update to our 2018 State of Terms Report: LP minimums, hurdle rates, average management fees, portfolio construction, and more

A little over two years ago, we published our State of Terms report, benchmarking a series of terms and trends in the venture capital industry. The report was a watershed moment of transparency for the industry, helping shed light on the opaque world of GP < > LP relations. Since then, the report has been downloaded thousands of times by GPs and LPs around the world.

We’ve continued to monitor the state of terms in venture capital since. Venture capital, like other private market investment strategies, tends to evolve slowly. The long timelines to prove fund performance paired with episodic fundraising, and the extended and perpetual time horizons of many institutional LPs, can lead to similarly gradual changes in LP agreements.

Given the chaos of 2020, we were curious to see whether GPs would adjust their terms in response. Would LPs request different protections in light of volatile public markets? Would the bulk of the venture industry adjust their terms due to the monopolization of capital by mega funds in 2020? Would we see a rapid change of any kind?

The short answer is, not really and not yet. There certainly has been some change in the state of terms, but it’s mostly been modest. For that reason we’re publishing this update as an article, rather than a full report. The article examines a subset of trends and terms from the original report that are worth discussing now. (For a broader take, read our analysis on VC trends of the last decade.)

We’ll continue to monitor the state of terms as we proceed through 2021, and we plan to release a full updated report once it’s warranted. For an explanation of each term or our methodology, please see the report.

Here’s where the market is today.

Management Fees are mostly steady, with blended rates trending down slightly

The average blended management fee is 1.93%, down from the 2.04% we reported in 2018. However the median blended fee is still exactly 2% — the average was pulled down by some GPs reducing annual fees a little more, a little faster. As an aside, we’ve also noted a small but growing roster of outlier funds setting exceptionally low (or zero) management fees, usually via alternatively structured vehicles (such as evergreens, which are excluded from the above benchmarks).

First year management fees remain higher than the blended rate, reflecting the front-loaded effort of investment sourcing and selection. The average first year management fee is 2.25%. This is mostly aligned with the average we found in 2018 of 2.3%. While we did not report the median first-year management fee in the 2018 report, it has held steady at 2.5%.

And likely no surprise to anyone — carry is unchanged, with the vast majority of funds setting carry at 20%.

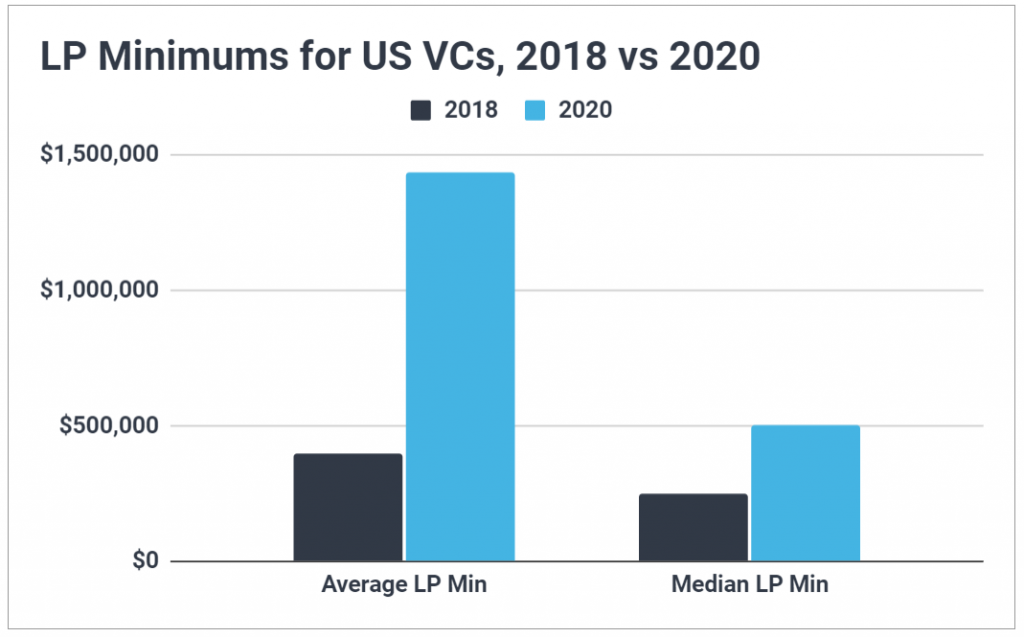

LP Minimums are trending up

Interestingly, stated minimum LP commitments have increased to a notable degree. The average LP minimum is $1.43M with a median of $500k, a significant jump from the $395k and $250k figures of 2018. For funds that differentiate minimums for individual investors and institutional investors, the average individual LP minimum is $420k with a median of $250k, while the average institutional LP minimum is $1.68M with a median of $1M.

While target fund sizes are trending up — which may explain some of the increase as GPs adjust their minimums to a corresponding degree — this is not enough to explain the increase entirely.

Of course, it’s worth recognizing that nearly every VC fund is able to accept smaller LP commitments at the discretion of the GP. In our experience, nearly every VC fund does accept a lower commitment from at least one LP — though their reasons for doing so vary. (The most common reason is an individual LP is a strategic value-add to the fund).

Hurdle rates on the decline

Hurdle rates are becoming less common and more modest. Since 2018, we have seen not only a reduction in the number of funds that set hurdle rates (down to ~15%), but also the rate of the hurdle. Whereas the average hurdle rate from our 2018 report was 7.25%, we now find the average is 5.85%. And whereas the median hurdle rate from 2018 was 8%, it’s now 6%.

Given the challenging fundraising climate in 2020 for most non-mega-sized VCs, this comes as a bit of a surprise: one might expect to see the adoption of more LP-friendly terms to help mitigate a tough fundraising climate.

Hurdle rates offer a form of protection to LPs in the cases of weak to middling performance from a fund. For emerging managers and funds seeking new LPs, the existence of a hurdle may tip the scales for a new LP. For many GPs, the expectation is that you’ll hit a 3X return net of fees and generate great performance for your LPs. But the reality is, many funds don’t achieve this. And reaching the common LP benchmark of public equity returns + 3 (for privates) becomes particularly challenging in a raging bull market. Having a hurdle rate helps demonstrate to LPs that you’re aligned with them and incentivized to deliver true venture-like returns.

That said, other factors could be driving the decline in hurdle rates:

- First, many asset classes are projecting lower forward returns, particularly in the public markets. If public markets anticipate weaker performance over the next decade, then there is less pressure to set a high hurdle rate in venture.

- Second, for most LPs, terms are secondary in selecting a manager. Sure, the terms should look market standard, and they certainly can’t be ridiculous. But if an LP believes they’ve found their next great manager out of a sea of thousands, the lack of a hurdle rate may be acceptable. Afterall — no one commits to a VC fund thinking they’ll only get the hurdle rate. GPs may recognize this and adopt the mindset of ‘why give away something I don’t have to.’

- Third, this could just be a lag as the market adjusts. VC fundraises last months to years, and many funds in market in 2020 may have set their terms pre-pandemic.

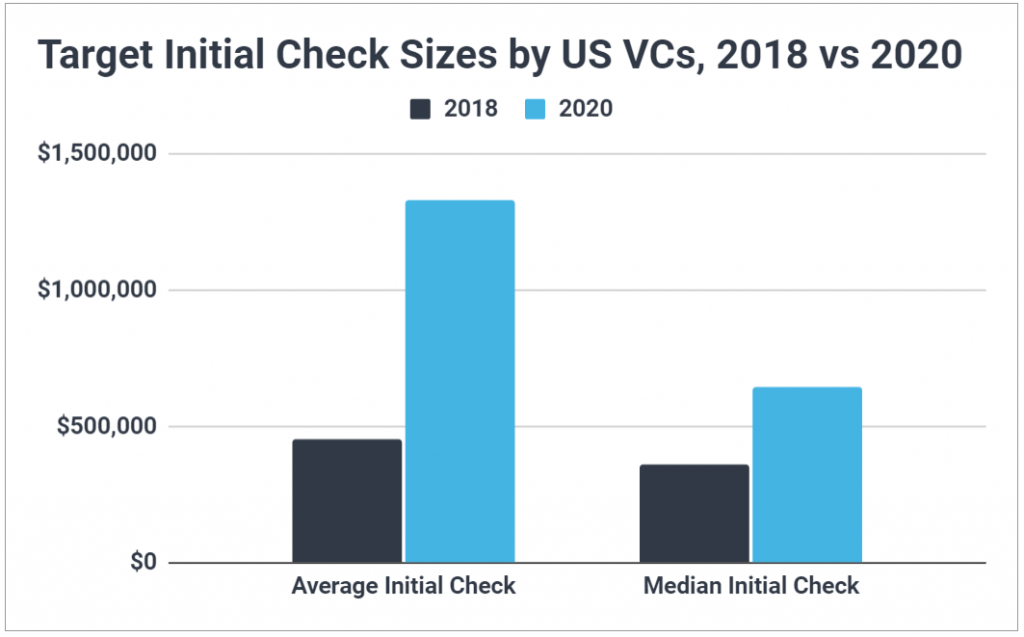

Portfolio construction expresses an appetite for greater flexibility

Some aspects of portfolio construction are unchanged, while others have changed a fair bit. The average and median target portfolio size is consistent with our 2018 report at ~29 and ~25 deals, respectively. The market reality is that funds vary widely across conviction and diversification portfolio strategies

Follow-on reserves are also roughly consistent with 2018, with a slight uptick: in 2020, VCs set aside an average of 48% of capital for follow-on, with a median of 50% reserved capital (versus 42% and 48%, respectively).

Initial investment per portfolio company has changed more significantly. In 2020, the average initial investment size was $1.33M with a median of $644k, both significant increases from our 2018 findings of $452k and $362k. As with LP minimums, the increase may be a result of target fund size growth. But it also may be fueled by a competitive deal environment, high valuations, and/or desire to acquire and retain more ownership in each deal.

More interestingly, we are seeing an increase in funds looking to originate deals across multiple stages. For example, a fund may market to LPs that it intends to originate ~20 Seed deals as well as ~5 Series A deals. Each of these deals would be new to the portfolio, versus follow-on.

The desire to invest across multiple investment stages may be tied to a corresponding rise in specialist and thematic investment strategies (another trend we’ve been monitoring). Specialist VCs invest in a specific and narrow set of sectors, industries, or business models (ex: energy, Bio+Tech). While Thematic VCs invest in a uniting theme of companies (ex: startups addressing climate change). Given the nature of these ‘thesis styles,’ GPs are likely to see sector-specific or theme-specific deals across a range of stages. Greater flexibility around target stage and portfolio construction may allow GPs to invest in a promising deal that is outside their core target stage.

Terms Take Time

The state of terms between GPs and LPs in 2020 was largely similar to 2018, with a few exceptions: LP minimum commitments have increased, hurdle rates have decreased, and some funds have sought greater flexibility in their portfolio construction.

And while emerging managers were certainly pummeled in fundraising last year (with many LPs fleeing to perceived safety in established mega funds), we’ve yet to see any major changes in the terms they offer to LPs in response. Notably, emerging managers tend to have less room for fee breaks or waivers than large incumbents, as the smaller AUMs constrain operating budgets by default. Tie in a history of outperformance among smaller funds and emerging managers, and GPs may argue they should not need to adjust their terms at all.

That said, adjustments to terms may simply be on a lag. Any funds that conducted a close in 2019 or 2020 are unlikely to modify their terms after. We may only begin to see changes as LPs, GPs, and their lawyers digest the post-pandemic market reality.