With a year’s worth of data since the pandemic took hold, what affect did COVID really have on venture capital markets?

It’s been one year since an emerging pandemic triggered a month-long stock market crash, and the economy began a swift contraction that would decimate main street far more than an apparently COVID-immune Wall Street.

At an aggregate level, venture capital markets, too, seemed to have secured a very early dose of the vaccine. Plenty of headlines noted the record-breaking year for VC across all classic measures (despite widespread predictions of an impending downturn).

But with a year’s worth of data in the books, we wanted to take a closer look at what exactly happened with the pandemic and venture capital, mapping activity quarter by quarter and diving into how VC firms reacted to such an abrupt disruption.

Q2 2020 Brought an Immediate Rush to Place Fresh Capital

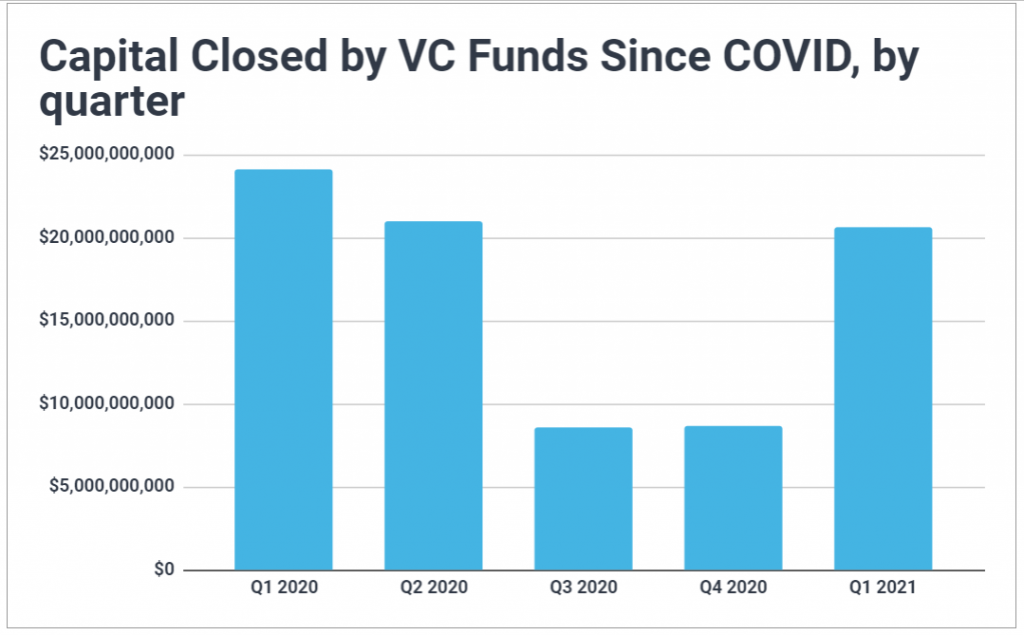

Early signs suggested LPs would be more cautious in their second quarter VC allocations. Similar to the Global Financial Crisis a decade earlier, there were assumptions around extreme uncertainty, the risk of the denominator effect as public equities plummeted, a strong chance of underlying portfolio companies quickly running out of cash, etc. Instead, venture capital firms closed $21B for their flagship vehicles in Q2. This figure was surprisingly on-par with Q1’s largely pre-pandemic $24B.

But, as we noted last May, virtually all of the capital raised in Q2 (80%) went into the pockets of a handful of mega funds. Those mega funds averaged a $2.1B haul from 157 LPs each and, on average, stepped up nearly half a billion dollars from their predecessor fund. That doesn’t even include the additional capital these funds often raise for concurrent opportunity or late stage vehicles, typically doubling the additional AUM they close.

Unsurprisingly, the concentration of capital in mega funds also meant a concentration of capital in Bay Area and New York VCs: in Q2, more than 80% of venture capital went to firms headquartered in these two top markets. Although only a modest increase over the 70% these regions garnered in 2019, it was a sharp jump from the 43% they closed in Q1 of 2020.

Generalists also experienced a surge in their share of capital. Whereas generalist VCs accounted for 53% of capital closed in 2019, they raised 76% of Q2 capital (and 94% of capital in March).

What drove LPs to allocate to venture in record numbers? For one, roaring (rather than the predicted crashing) public markets meant LPs could increase assets in their venture sleeve while maintaining their portfolio construction strategy. Billionaires alone saw their wealth swell 27% from April to July. Coupled with the increased liquidity brought by SPACs and a low-interest-rate-driven appetite for private market returns, more capital than ever was looking for a home in venture capital.

But, with the initial volatility brought on by the pandemic spooking investors, asset allocators were cautious to select any funds seen as too risky — instead opting to lean into larger, later stage vehicles, under the logic that no one was ever fired for hiring IBM (or investing in Sequoia).

| Mega Funds | Bay Area & New York VCs | Generalist VCs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 43% | 70% | 53% |

| Q1 2020 | 78% | 43% | 86% |

| Q2 2020 | 80% | 81% | 76% |

| Q3 2020 | 50% | 71% | 34% |

| Q4 2020 | 48% | 71% | 53% |

When analysts first noticed Q2’s strong fundraising numbers, many explained it away as a result of the time lag inherent in VC fundraising: since firms spend months (if not years) on the fundraising trail, most of the Q2 closes actually began long before the pandemic became a factor.

And while there’s certainly some validity to that hypothesis, there’s also evidence that venture capital firms did in fact react to the pandemic as early as Q2, accelerating their fundraising cycles to close earlier than previously planned with more capital than previously planned.

According to our data, 65% of funds closed in Q2 were accelerated raises (i.e. there was less time since the last fund than was historically typical for a given firm). Although this is reflective of the broader trend of contracting fundraising cycles in VC, it’s nonetheless telling that the average mega fund closed in Q2 came just 2.5 years after its predecessor was launched.

Overlooking the fact that 2.5 years is a rather short period of time before requiring a fresh billion dollars (bearing in mind many of these VCs don’t actually need a capital injection, they’re loading up on dry powder), such a timeframe is hardly sufficient to provide LPs evidence of successful deployment in their last fund. In 2.5 years, not only will a VC’s predecessor fund have little to no exit data (meaning any performance data reported to LPs is driven entirely by the VC’s own valuations of their portfolio), but it may also still be actively investing in new companies.

Second Half of 2020 Cooled Off

Compared to the frothy Q2 for VC fundraising, the third and fourth quarter cooled off significantly. Venture firms closed just $8.6B in each of these quarters, with a more historically-balanced 50% going to mega funds, 70% going to Bay Area and New York VCs, and more modest average step-ups of $65M-$80M.

A cool-off is hardly shocking given the sheer number of name-brand firms that closed in the first half of the year — our estimates suggest nearly 15% of the top 50 VCs in terms of mindshare successfully raised a fund in Q1 or Q2.

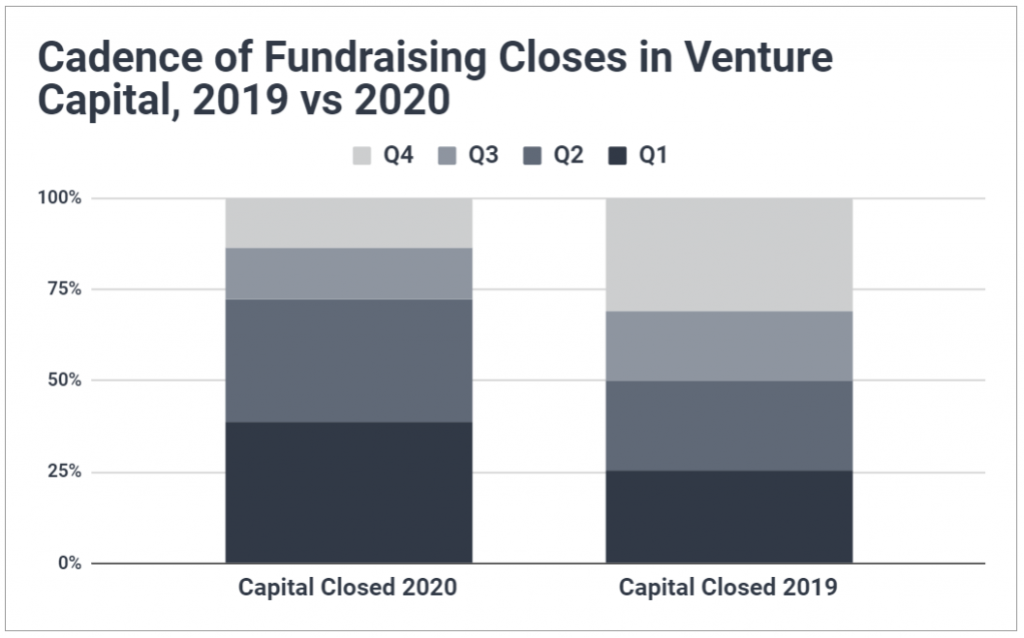

It’s also relevant to note VC fundraising generally cools off in the middle of the year, with most closes coming towards the beginning or end of the year. However, 2020 proved to be exceptionally weighted to the 1st half of the year. Whereas half of the yearly fundraising total in 2019 came in Q1 or Q2, almost three-quarters of 2020’s total was closed in the first half.

The abnormal concentration of closes in the beginning of the year further supports the narrative of accelerated fundraising cycles in response to the pandemic: if firms that were on the fundraising trail and planning to close in the second half of the year pushed up their timelines to close in Q2, that would contribute to H1-heavy levels for 2020.

Of course, not all VCs are capable of accelerating a fundraising close — most managers struggle to reach their targets on their planned timeline at all. The VCs closing in the second half of the year, then, were more likely those without extensive LP networks (i.e. emerging managers). This would explain why emerging managers (Funds I-III) accounted for just a quarter of capital closed in Q2, compared to nearly half of that closed in Q1, Q3, and Q4. To punctuate this point even more, in March alone, emerging managers fell to just 7% of capital closed.

First Signs of the “New Normal”

Although data for Q1 2021 is still preliminary, so far this year is looking more like the first half of 2020 than the second.

Of the approximately $20B that’s been closed by flagship funds since January, 77% has gone to mega funds and less than a third has gone to emerging managers.

Since this quarter’s data is now reflecting closes from VCs who actually began the fundraising process during the pandemic, early signs are suggesting 2020 may have ushered in a new era for venture capital — one where mega funds and established VCs dominate the capital landscape, slowly crowding out the emerging managers who have mostly defined VC to this point.

The consequences of this changing dynamic can only be hypothesized. But given monopolization of any kind is generally bad for innovation and those outside the majority, there isn’t much reason to expect this change to bring a more equitable distribution of capital to the most innovative entrepreneurs.